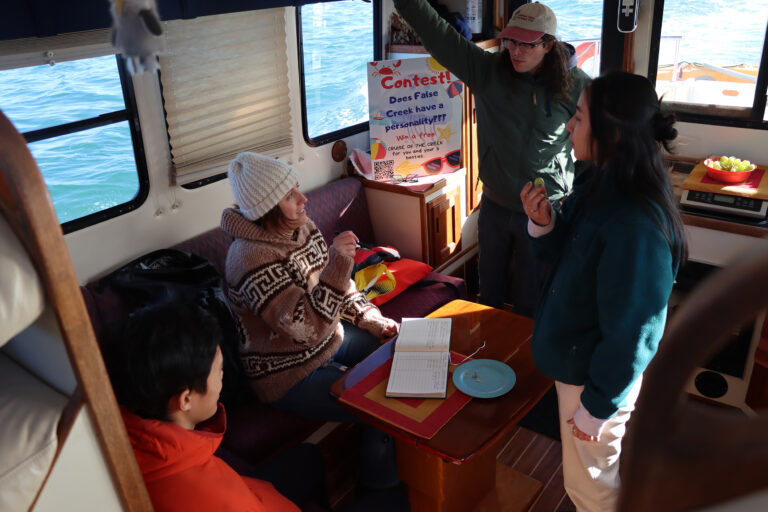

When you step aboard Zaida Schneider’s boat, you become enveloped by a sense of warmth and belonging. As you make your way inside the cabin, you’re greeted with a guest book filled with the memories of past visitors and surrounded by carefully placed photographs of loved ones and trinkets, all of which reflect his life and deep regard for the water.

Lately, his focus has rested on the waters of sən’a?q w (hən’q’emin’əm’) / Sen’ákw (Skwxwú7mesh), colonially referred to as False Creek. Since time immemorial, False Creek has been an important gathering place for the Xʷməθkʷəy̓ əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and Səlil̓ilw̓ ətaʔɬ (Tsleil-waututh) Nations, as the protected, shallow waters offered an optimal location to fish and forage within the intertidal zone.

In 2021, Zaida and his friend Tim Bray co-founded False Creek Friends Society – a nonprofit that aims to restore False Creek in accordance with the latest marine research and in ways that align with First Nations stewardship values.

They were spurred to develop False Creek Friends Society out of a perceived necessity. In 2020, Zaida returned to Vancouver after a twelve year period sailing abroad. He soon came to realize that there was little regard for False Creek in terms of its ecological importance. He says there was a lack of direction given to sailors on how to use the water respectfully, particularly when it comes to avoiding pollution.

“There [was] no sense of the marine environment being special here…A complex ecosystem, doesn’t speak human language, it has its own language. But with enough work, study, and community science projects we can learn what it’s actually saying, because it is speaking. It has a voice, it has a personality, and we’re starting to introduce that person to the people of Vancouver and beyond.”

For a long time, that non-human language False Creek speaks was ignored.

By the late 1800s, as more settlers began to occupy the area, the Xʷməθkʷəy̓ əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and Səlil̓ilw̓ ətaʔɬ were forcibly removed from their territories and on to reserves. Gradually, False Creek’s tidal flats were heavily polluted and industrialized, as they were surrounded by sawmills and logging roads. In 1912, The City of Vancouver and the Canadian Northern Railway took it upon themselves to forever alter this body of water by draining its easternmost end. False Creek, which had previously extended to present-day Clarke Drive, was filled in to what is now Main Street to accommodate railway expansion.

In spite of the damage inflicted upon this ecosystem, False Creek’s biodiversity continues to persist. If you spend enough time walking the docks of False Creek you are likely to observe large schools of Northern anchovy, perhaps a couple of mottled and ochre sea stars, a plethora of Pacific harbour seals, Dungeness crabs, and if they happen to enter the shallows, you might catch a glance of a North Pacific spiny dogfish. In recent years, even Pacific herring have started reentering False Creek to spawn, thanks to the restoration efforts of Squamish Streamkeepers.

Contrary to popular belief, False Creek is teeming with life and consciousness. Zaida wants community members to connect with False Creek in a way most haven’t before – acknowledging its personhood and building a relationship with it.

“When you walk along the beach at low tide in the sun…when your shadow falls upon barnacles that have been dried out…they all go ‘ahhhh’. You can hear them exhale. They’re aware of what’s going on in their environment and awareness is really the foundation of personhood. If we ignore that complex, interdependent awareness, we’re doomed.”

It’s through nurturing a personal connection with the water, that one becomes personally invested in its well-being. In 2021, Parks Canada set aside $130 million to work towards the creation of a network of national urban marine parks by 2030. Zaida hopes that False Creek will be designated one of these urban marine parks, in order to facilitate long-term stewardship.

So the next time you’re walking along False Creek, take a moment to pause and reflect. Think about what these lands and waters have been and what they could be again. While wandering, if you happen to see a False Creek Friends Society boat tugging along, feel free to give Zaida a friendly smile and a wave.