December 16, 2025 – by Aleesha Switzer

Hey everyone, it’s Aleesha! Welcome to my first blog post for CPAWS-BC. I started here just about nine months ago and there were a lot of questions swirling around, like when will land use planning launch? What areas will be considered? What will the timeframe look like? Can I be honest with you for a second, CPAWS-BC supporters? I didn’t really know what a land use planning process was! If you’d asked me then what being part of land use planning in Northwest BC would feel like, I’m not sure I could have answered. Technical? Important? Complex? All true. But now that I’m in it, I can also say it has been inspiring, and has changed the way I view my work and how important it is that we continue to have the support of folks like you.

This post is a behind‑the‑scenes check‑in on my experience so far—how this work came together, why it matters, and what it’s been like to show up as a voice for nature in a process that’s shaping the future of the northwest.

Why the Northwest, and Why Now?

In May 2025, Premier David Eby announced the Northwest Strategy, an ambitious commitment to advance reconciliation, conservation, and economic development together. The goal was not to choose one over the other, but to move them forward hand‑in‑hand. Land use planning, as I have since discovered, is a process that defines what can and cannot take place on the land, and where. Zones are defined that make it clear where industry can develop and to what extent, and where protected areas are set aside. The northwest contains some of the most significant potential for mining projects in BC, and is a critical component of the Province’s economic strategy. In this part of BC, many existing land use plans were created without First Nations’ input, or did not meaningfully consider First Nations’ rights. Launching land use planning processes that include First Nations as government-to-government partners is an act of reconciliation. In terms of conservation, the opportunity for protection is the biggest we will see in a generation, and the significance cannot be understated.

What makes the northwest so remarkable is its wilderness. These are some of the largest, most intact, and truly wild landscapes left in British Columbia. The northwest is a place of extraordinary beauty and ecological value, supporting healthy salmon populations, species at risk like Caribou, and a whole host of interconnected plants and animals. We know that setting aside protected areas for nature is critical to maintain healthy biodiversity and ecosystems, and is an important part of responding to the urgent realities of climate change. Responding to this, the BC government joined Canada and nations around the world in the goal to protect 30% of our land and freshwater by 2030. The potential for protection in the northwest is staggering. More than 4% of the entire province could be protected through this work alone. At the end of 2025, 15.9% of BC is protected, with another 4% only partially protected. Being part of conversations that could help protect these places has been a tremendous privilege.

Early Stages – the First 5 Months

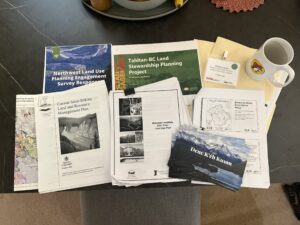

As a CPAWS‑BC staff member, most of my day‑to‑day work happens remotely from my home in Abbotsford, BC, on the traditional territories of the Stó:lō people. The first few months of work after the land use planning projects in the northwest were announced was largely virtual. Working alongside CPAWS-BC’s trusty Conservation Specialist Johnny Mikes, (honestly, folks, with the lifetime of experience in the north he brings to the team he has been a lifesaver) we learned about the planning areas, built campaigns for public engagement, and, overall, worked to figure out where and how CPAWS‑BC could best contribute.

CPAWS‑BC has a long‑standing relationship with the Kaska Dena First Nation, and we’ve advocated for the protection of their Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA) Dene K’eh Kusan (DKK) for many years. The northwest land use planning marked a pathway for provincial law to finally recognize DKK as a protected area. I have been engaging with the Kaska Dena team to better understand how we can support their vision for Dene K’eh Kusan, while also advocating for nature across the broader northwest planning areas.

A few things have made these land use planning processes different from what has been done in the past. First, four separate land use planning processes were launched simultaneously, each with their own government-to-government agreements between BC and First Nations. That means each process has its own engagement plans, phases, goals, etc. Second, a timeline of 12 months was established for the four plans to go from launch to final product approval. In the 1990s and 2000s, land use planning processes across the province often took several years (sometimes more than 10!) to reach completion. This accelerated timeline reflected two key aspects of the process: 1) The desire to have certainty for economic development quickly, and 2) The extensive preparation already done by the Nations. A critical piece of this work is the inclusion of IPCAs. Many First Nations have spent years—sometimes decades—developing stewardship visions for their territories. These visions are articulated through IPCA declarations and brought into the land use planning process as essential guiding documents.

These land use planning processes are taking place during a serious time and budget crunch in BC. We knew from the start that we would need to adapt and respond quickly when opportunities arose. What we didn’t expect was a BC GEU strike to take place for a record-breaking 8 weeks, cutting that time available for the already-ambitious 12 month processes even shorter. While we waited for updates week over week, I wondered what role CPAWS-BC could play in land use planning.

The Voice for Nature

This idea of CPAWS‑BC as a voice for nature is something I had heard, but it wasn’t until the land use planning engagement sessions began in earnest this November that the role really came into focus. I attended sessions for the three largest planning processes in the northwest, the Kaska-BC project, Tahltan-BC project, and the Taku River Tlingit First Nation-BC project. In each scenario, the BC government staff and First Nations leadership invited “stakeholders” to share their values and interests regarding these places. Stakeholder, in my opinion, is a rather dated term here, meant to include anyone who has a direct interest in the outcomes of the process. These sessions, both online and in-person, brought together a wide range of participants to hear updates from the BC government and First Nations about the goals, visions, and direction of the land-use planning process. Stakeholders were then invited to share their own perspectives—what mattered to them in these landscapes and how they hoped the planning process would move forward. The room included representatives from many sectors and industries, all with strong opinions about how these vast areas of the northwest should be managed.

Looking around the rooms, I was pleased to see some familiar faces – groups like the BC Wildlife Federation, Outdoor Recreation Council, and Wilderness Tourism Association were also present as stakeholders. These organizations spoke about how their respective industries benefitted from healthy ecosystems in the planning areas. Seeing that overlap and shared commitment to protecting nature was genuinely encouraging.

Conversely, the majority of participants in the room were representatives of extractive industries – primarily the mining industry. These folks were advocating for more exploration, more mining, and less protected areas across the board. Now, I want to make the record clear for a moment – we support the Northwest Strategy’s three pillar approach of reconciliation, conservation, and economic development needing to occur hand-in-hand. The land use planning areas needed to contain space and opportunity for all aspects of the strategy to be realized. What surprised me the most about these stakeholder engagement sessions was not the diversity of viewpoints, but the absence of voices.

Given how ecologically significant these areas are, their importance for biodiversity, for species at risk like northern caribou, for headwater streams that support abundant populations of salmon, for climate mitigation and refugia, and for protecting some of the last truly wild landscapes in the province, I expected to see dozens of environmental organizations from across BC and Canada lined up to participate. Instead, when it came to simply being there to speak for nature, CPAWS-BC was often one only of a small handful of organizations in the room. By sheer numbers, industry, particularly the mining sector, had the strongest presence in every room. It struck me then why the role of CPAWS-BC being the “voice for nature” matters so much in these processes.

I left those sessions feeling incredibly proud of the role we’re playing, and deeply grateful to you, our supporters. Your support is what allows CPAWS-BC to show up in these spaces, to advocate for Indigenous-led conservation, to speak about the importance of connecting and protecting adjacent landscapes, and to ensure that the ecological value of the northwest is not overlooked. These stakeholder engagement sessions were a powerful reminder of how conservation advocacy actually happens, not just through reports and campaigns, but by being present, prepared, and willing to speak up when it matters most. As this work continues into the new year, there will be more opportunities for engagement and for supporters like you to add your voice alongside ours. I now understand more clearly than ever how essential that collective voice for nature truly is.

Thank you for standing with us, and for helping make this work possible. Stay tuned for more updates in 2026!