BC’s Glass Sponge Reefs Need a Bigger Buffer

Ocean Campaigner

Deep under the ocean waters off of BC’s Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound live rare and delicate glass sponge reefs. While glass sponges are found all over the world, it is mainly on our coasts that they form intricate reefs. CPAWS-BC has been advocating for the protection of glass sponge reefs since 2001. In 2017, the Government of Canada established the Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound Glass Sponge Reefs Marine Protected Area Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) to safeguard these fragile features from harmful human activities. But new research published in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series suggests that these current protections may not be enough to prevent glass sponge reefs from harm.

Most marine sponges are soft and squishy, feeling much like the sponges we use to clean our kitchens and bathrooms. However, glass sponges absorb silica from the water to form their glass skeletons, giving them hard bodies but making them extremely fragile.

The earliest fossils of glass sponge reefs are 220 millions years old, spread out over a 7000 kilometre stretch of Central Europe. However, 40 millions years ago they disappeared from the fossil record and were thought to be extinct.

But in 1987, a team of Canadian scientists mapping the seafloor discovered living glass sponge reefs 200 metres below the ocean surface of Hecate Strait. For them, this discovery was like finding a herd of living dinosaurs.

ESSENTIAL TO THE ECOSYSTEM

Far from just being beautiful and rare, glass sponges are also integral parts of the ocean ecosystem.

Glass sponge reefs provide shelter for bottom-dwelling creatures such as rockfish and prawns.

Fishing activity can cause severe harm to these fragile habitats. Prawn and crab traps drop down and crush glass sponge reefs. Bottom trawling of heavy nets dragged along the seafloor destroy everything in their path while kicking up clouds of disturbed sediment. The Marine Protected Area regulations protect the reefs themselves from bottom-contact activities such these. However, nearby fishing activity kilometres away can still be deadly.

Glass sponges are filter feeders. They do this so efficiently that 95% of bacteria are filtered out, cleaning the water. In fact, a single small reef can filter enough water to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool in less than 60 seconds! Furthermore, the nitrogen waste they excrete acts as a fertilizer for plankton.

When these storms of sediment kicked up be bottom trawling roll over glass sponge reefs, they are triggered to stop filter feeding and absorbing oxygen. The glass sponges choke and can even starve to death.

NEW DISCOVERIES

But animals behave differently depending on where they live and no experiments had been conducted on the Hecate Strait sponge reefs. Research released last year shed light on this mystery.

Living 200 metres below the sea surface, the Hecate Strait sponges are too deep for humans to dive to. To reach these depths, a remotely operated vehicle or ROV was used to carry out the experiments. Remotely controlled from a ship on the surface, the robot operated like an underwater drone, but with the bonus feature of mechanical arms.

The ROV placed thermistors, special devices used to measure water flow, inside the opening on top of the sponges to measure how much water the sponges were filtering for feeding.

To measure the sponges’ reaction to sediment, the ROV’s arm used a modified ice scoop to spread sediment over the sponge.

“Just a little bit of sediment actually stops the sponges from feeding for six to 12 hours. If that continues for long enough, that could lead to health problems and even death,” said Carlo Acuna, Ocean Campaigner, CPAWS-BC

North Shore News

The scientists found that the glass sponges stopped filtering water after even small increases in suspended sediment. Bottom trawling activities kick up much more sediment than the Hecate Strait glass sponges can tolerate.

The suspended sediment created from a three hour bottom trawl could stop glass sponges from feeding for six to 12 hours. Fishing activities around the marine protected areas could deprive Hecate Strait sponge reefs of nearly one thirds of their food supply, stumping their growth and hindering reproduction. Extended exposure to sediment could lead to death.

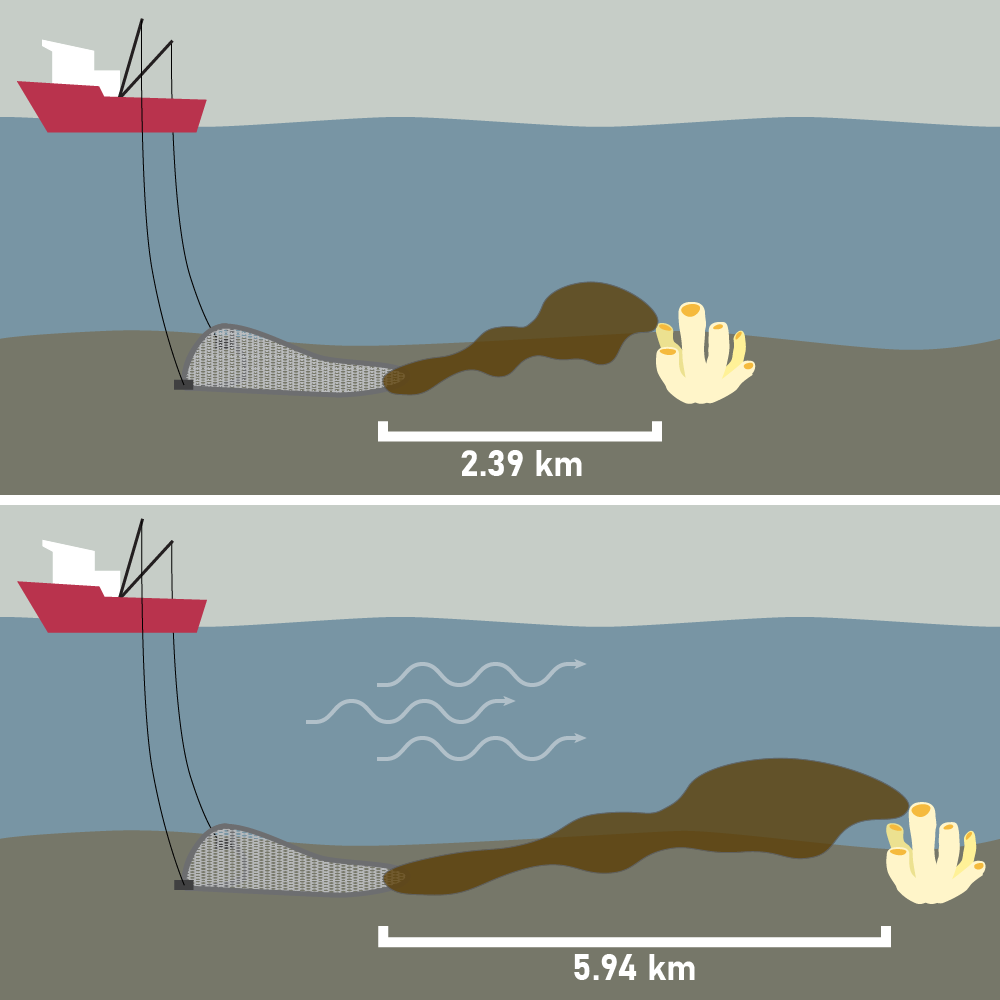

Furthermore, models indicate that suspended sediment from trawl fishing as far away as 2.39 kilometres can cause glass sponges to stop feeding. With the right tides and current, this harmful distance can be as far as 5.94 kilometres.

MORE PROTECTION NEEDED

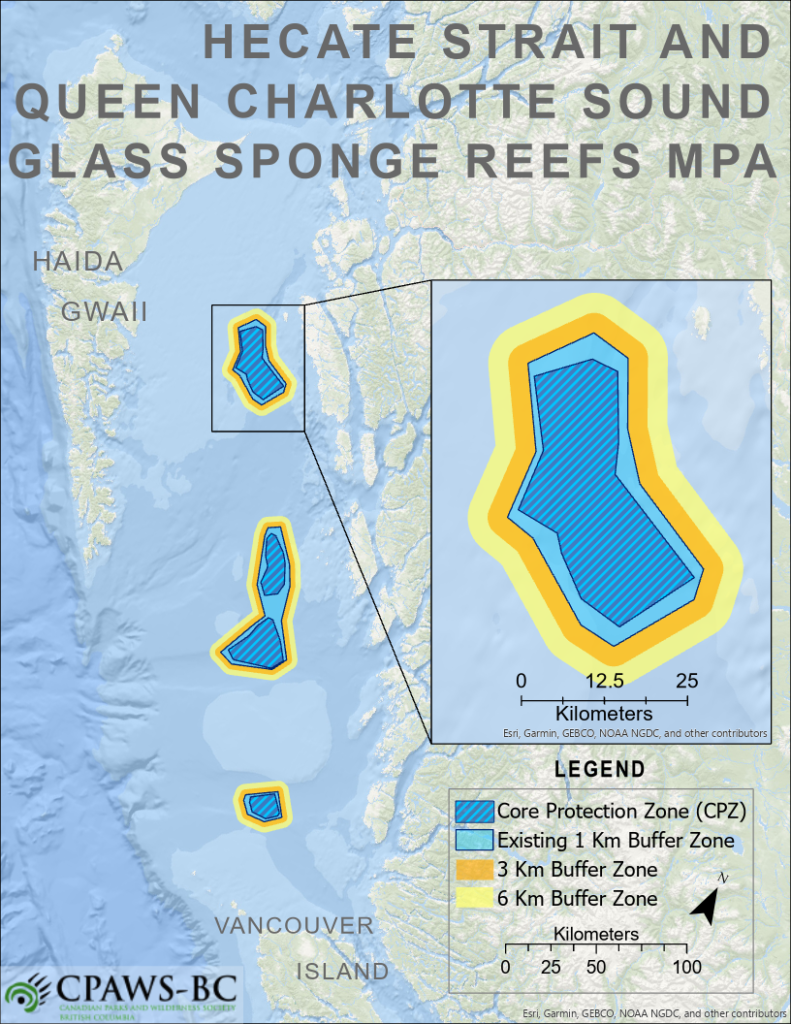

The Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound Glass Sponge Reefs Marine Protected Area currently provides a one kilometre buffer zone around each reef where no bottom contact activity is allowed. This new research proves that these restrictions are not enough to protect these global treasures.

“Trawling is the biggest bottom contact fishing activity,” Carlo Acuna, CPAWS-BC Ocean Campaigner

The Squamish Chief

Although the glass sponge reefs found in Howe Sound and the Georgia Strait have been found to have a stronger tolerance to sediment, their buffer zones are only a paltry 150 metres wide and drastically insufficient.

New regulations are needed to increase the Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound Marine Glass Sponge Reefs Protected Area buffer zones to at least three kilometres and as much as six kilometres. This will only increase restricted bottom fishing areas in B.C.’s ocean by 0.6% while ensuring the health of the valuable marine species supported by these reefs for generations to come.

The glass sponges in Howe Sound and Georgia Strait look to be more resistant to sediment. Using the precautionary principle, we are proposing an increase of the buffer zones here beyond the current 150 metres until proper ground truthing research has been carried out and the local threats have been assessed.

CPAWS-BC has been working since the early 2000s to protect B.C’s glass sponge reefs. We celebrated when the Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound Marine Protected Area was created in 2017. In 2017, we supported the nomination of glass sponge reefs for UNESCO World Heritage Site status. With your help we can add further protections, ensuring these wonders found nowhere else in the world are sufficiently preserved for generations to come.

Take Action Now

Tell Fisheries and Oceans Canada to expand the protective boundary prohibiting bottom-contact fishing, industrial activity, and seabed mining around each glass sponge reef.