CPAWS welcomes protection of Howe Sound glass sponge reefs

CPAWS welcomes protection of Howe Sound glass sponge reefs

March 6th, 2019

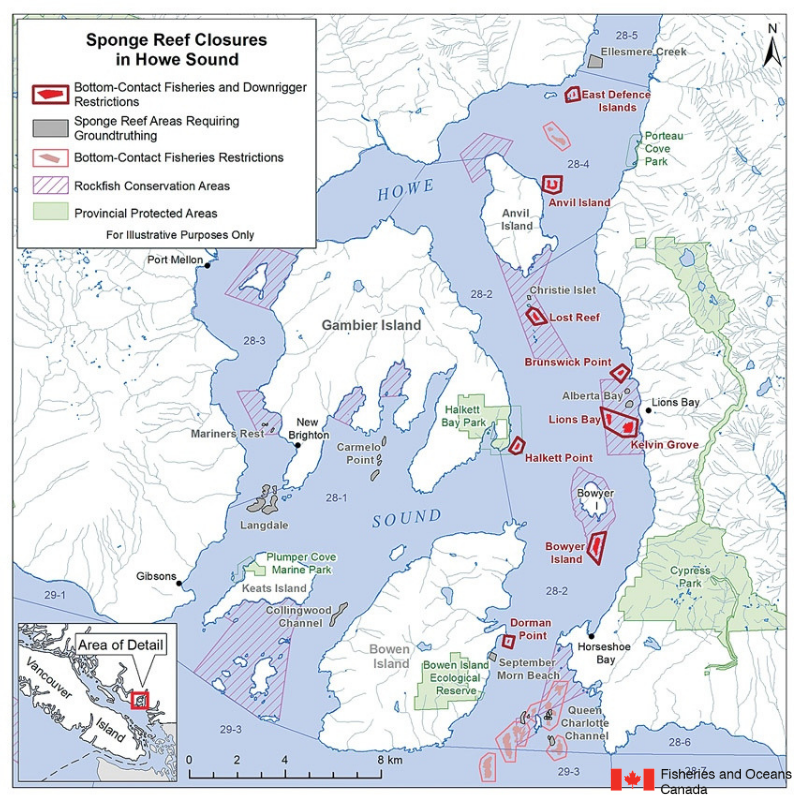

Vancouver, BC – The Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society is very pleased to see the eight new marine refuges announced today, protecting nine of Howe Sounds newly discovered Glass Sponge Reefs from all bottom-contact fishing, by the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, and the Canadian Coast Guard.

“The Howe Sound glass sponge reefs are an ecological treasure on the door step of one of Canada’s largest cities. They are a very important ecological feature in Howe Sound, that provide both habitat for many species and ecological services including filtering of ocean water,” said Sabine Jessen, National Director of the Ocean Program for CPAWS.

“CPAWS has been involved in the protection of glass sponge reefs on the BC coast for almost two decades, since the first reefs were discovered in Hecate Strait in the late 1980s,” said Jessen. “Living glass sponge reefs date back to the Jurassic era, and are living dinosaurs on our Pacific Coast. We have a global responsibility to ensure their long-term survival.”

“In order to ensure their survival, we are pleased to see that the Minister has announced a number of protection measures, including a 150 metre buffer zone to prevent bottom trawling from both destroying the reefs and from smothering them with sediment, as well as prohibitions on all bottom contact fishing, which can have a severe impact on fragile glass sponges,” noted Ross Jameson, Ocean Conservation Manager, CPAWS-BC.

“We remain concerned that anchoring has still not been addressed in the protection measures for these reefs, and the previous nine glass sponge reefs in the Strait of Georgia that were previously protected,” noted Jessen. “CPAWS will continue to work with DFO and other agencies to ensure that all threats to the reefs are addressed.”

“CPAWS would also like to take this opportunity to recognize the efforts of local groups in Howe Sound who have worked tirelessly to document the Howe Sound glass sponge reefs and to advocate for their long-term protection,” noted Jessen. “We would especially like to recognize Glen Dennison for his many years of work, and to commit to him to assisting with the protection of the additional glass sponge reefs that he has identified in Howe Sound.”

“While we are pleased to see the glass sponge reefs in Howe Sound, like those before them in the Strait of Georgia, being designated as marine refuges, we hope that in future they will form the backbone for a network of MPAs in this region,” added Jameson.

-30-